Policymakers increasingly see AI as a tool for accelerating scientific discovery, and in turn generating a new wave of innovations that tackle critical societal issues and boost productivity. Recent policy announcements from the UK and EU set out aspirations to promote widespread adoption of AI in science. Between that ambition and the reality of AI for science sits a gap between what’s technically possible and what’s scientifically useful.

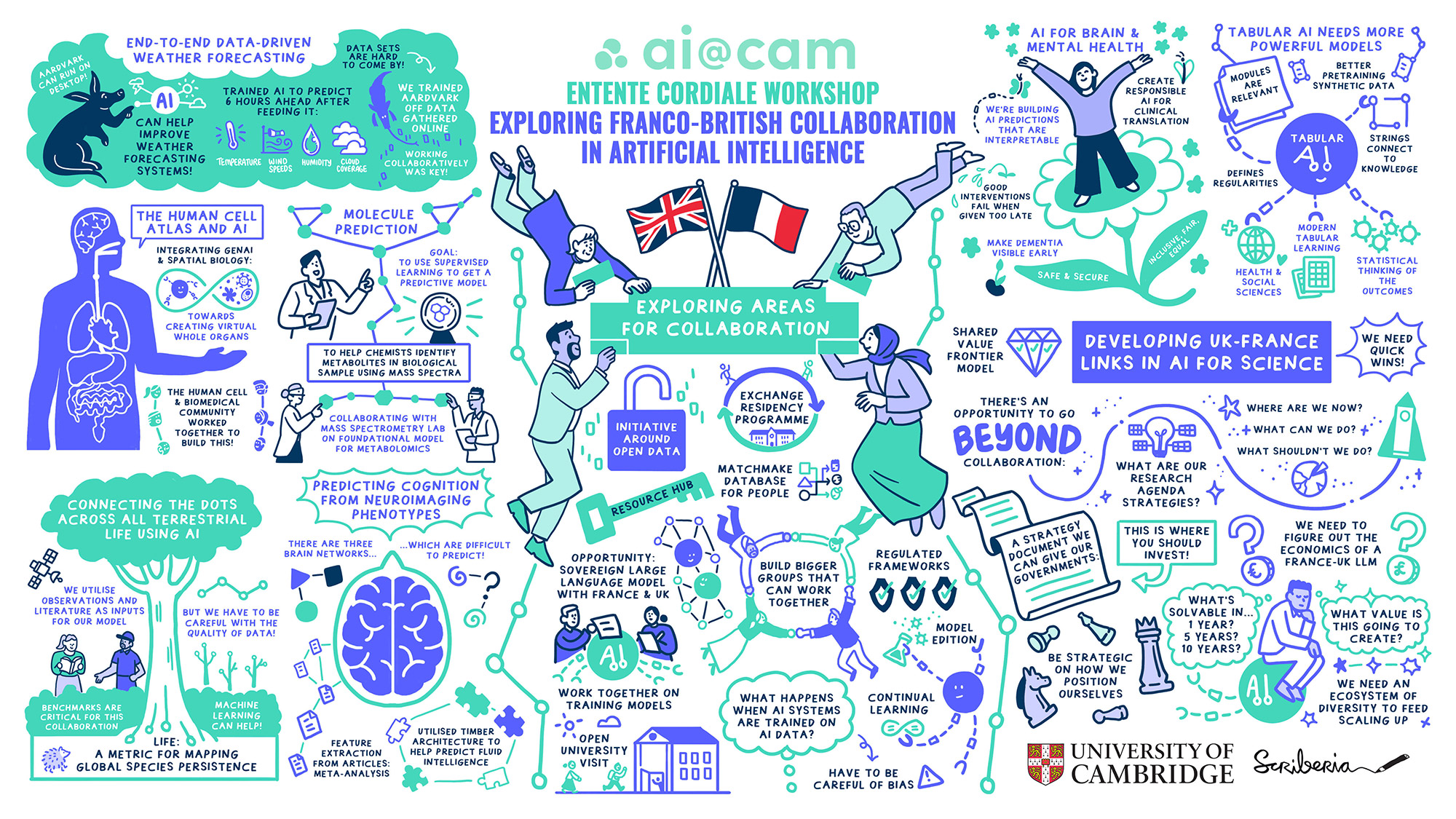

On 20 November, as part of an emerging UK-France collaboration in AI, ai@cam brought together researchers working at the intersection of AI and science. The conversation moved across different problems: how do you forecast weather without traditional numerical weather prediction? How do you model how a drug affects tissue structure? How do you predict molecular structures from mass spectrometry data? How do you quantify the extinction impact of agricultural land use? How do you extract reliable insights from the neuroscience literature? How do you diagnose dementia earlier? These aren’t separate questions. They’re connected by something deeper: a rethinking of how the scientific pipeline works, from data to actionable insight.

A machine learning system that ingests raw weather observations and produces forecasts without any dependency on traditional meteorological models represents a shift in what becomes possible. A model trained on readily available cognitive tests predicts Alzheimer’s progression more accurately than expensive brain imaging, and it works in real clinics with messy, incomplete data. A geospatial model quantifies the biodiversity impact of the food we eat, allowing decision-makers to interrogate the environmental impact and security of agricultural systems.

These projects illustrate how AI can shift the landscape of scientific opportunities, and the practice of science itself.

Methodological bottlenecks and a research agenda in AI for science

Get close to how AI is being deployed in science, and you see this is hard in ways that don’t resolve with more compute or bigger models.

For example, there are long-standing challenges in uncertainty quantification that have new manifestations in AI for science. Researchers need confidence intervals – on graph predictions, on tissue models, on extinction estimates – that help them understand how to interact with their analyses. This is difficult to get right, especially in complex systems operating across different scales.

Then causality. Multiple different models can fit the same data equally well while making contradictory causal claims about what’s happening in a system. Science needs to distinguish real causal links from statistical artefacts.

Science produces a wide range of data types – satellite data, time-series measurements, sparse spectra, fragmentary observations, and tabular data – which is often not easy to work with for AI. Most machine learning assumes regular, dense arrays. In response, new architectures are needed to fuse heterogeneous data without losing signal, and these need to work with missing data, because real science is messy. There’s a provenance problem too. As AI-generated content becomes more common, there is a risk that synthetic data launders back into training sets, and the ground truth scientists are working from gets contaminated.

Challenges in interpretability and validation can be found across areas of science. A model that predicts well on a benchmark but works poorly when decisions depend on it is not useful in deployment. Domain experts often want to understand why a prediction was made, not just that it was made, and when to trust it. Strategies for embedding domain knowledge become necessary to advance scientific understanding: AI for chemistry using loss functions informed by chemical validity; tissue models in life sciences being developed with geometric priors that respect how tissue behaves; weather models making use of conservation laws. Constraining models with domain knowledge helps build in interpretability; if a model respects known principles, scientists can reason about its predictions. It can also support validation: if a molecular prediction violates basic chemistry, something is likely to need further investigation; if a weather model violates conservation of energy, the forecast seems likely to be unreliable.

These problems are methodological, not computational. They don’t solve themselves at scale.

Spaces for interdisciplinary innovation in AI for science

Today’s research and policy conversations about AI for science are often dominated by a particular strategy: scale. Bigger models, more parameters, more compute, more investment capital. That approach has advanced the field and produced impressive capabilities, but it’s not the only research strategy, and whether this strategy will move the frontier forward is an area of debate.

Many methodological problems in AI for science are not primarily solved by scale. Uncertainty quantification doesn’t become easier with larger models. Data integration across heterogeneous sources doesn’t resolve through parameter count. Interpretability for domain experts isn’t a problem solved by more GPUs.

Universities are spaces to ask questions where the economic return is unclear, but the problem is real. They can build infrastructure – open foundation models for geospatial analysis, secure data environments, living databases of evidence – that benefit a broad research ecosystem rather than a single product or company. They can invest in understanding why things work, not just whether they work. They can build for resource-limited settings: weather forecasting systems for regions without expensive supercomputers, diagnostic tools for under-resourced clinics, molecular prediction methods accessible to chemists without large compute budgets. Universities can also hold space for reproducibility and validation; particularly important when synthetic data contamination, model drift, and evidence fabrication pose challenges to the integrity of the information ecosystem.

Innovation often comes from asking different questions at the intersection of different domains. This is why open science and collaborative frameworks matter. When researchers from different fields share methods, data, and insights freely, solutions emerge that no single discipline could generate alone. A technique from computer vision might unlock interpretability challenges in molecular prediction. A causal inference method from economics could address uncertainties in climate models. A data integration approach from neuroscience could help geospatial analyses. These cross-fertilisations happen when there are spaces, such as conferences, shared data infrastructures, collaborative networks, where diverse expertise meets. Universities are positioned to create those spaces and ask these interdisciplinary questions that will drive forward the science of AI for science: How do we understand causality with limited data? How do we build tools for settings with minimal infrastructure? How do we quantify uncertainty honestly? How do we maintain evidence integrity at scale?”

Progressing AI in science

Consider what happens when these methodological challenges are unblocked. A climate model that respects conservation laws isn’t just more accurate; it’s interpretable in ways that matter for policy. A drug model that quantifies its own uncertainty lets a researcher know when simulation is enough and when they need the wet lab. A molecular prediction system that embeds chemical validity catches its own errors before they propagate. The economics of experimentation change. Scientists have more options for testing hypotheses computationally before committing resources to physical experiments. Knowledge becomes less dependent on having institutional resources or expensive infrastructure. These are shifts in how science works.

Realising this potential requires a different approach to innovation. One grounded in understanding the specific problems that emerge when AI meets science, from uncertainty in complex systems, to causality with limited data, to dealing with messy data. Universities are positioned to do this work: to ask the hard methodological questions, to build tools that respond to scientific needs, to ensure these innovations work across different contexts and resources. The transformation of science through AI depends on whether we can work with deeper attention to scientific problems, in dialogue with the disciplines and communities that understand them.

Thank you to colleagues from Cambridge, Oxford, and Paris who participated in the Entente Cordiale workshop on 20 November 2025.