Ever since Dr Emily Lines walked through the woods each day on her way to school, she’s been fascinated by forests. Today, she’s using ground-breaking AI methods to safeguard the future of our trees.

Over the past few years, Dr Lines has been developing a pioneering research programme with her team in the Department of Geography to improve how forests are monitored through unprecedented insights into the minute details of forest structures.

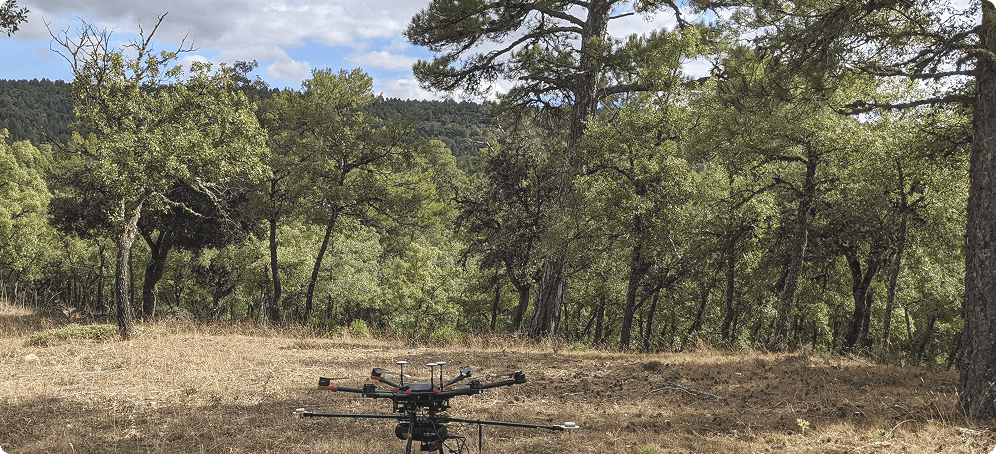

Drawing on high-resolution laser scanning technology from the ground and drone images from the air, her team has been building up detailed millimetre-scale reconstructions of forest canopies – down to the level of individual leaves and twigs – to create 3D reconstructions of woodland areas across the UK and Europe. They’ve been collecting billions of data points – known as ‘point clouds’ to help measure biodiversity and improve the accuracy of carbon accounting.

Mapping even relatively small woodland areas is time-consuming and labour-intensive work (it takes around 30 minutes to scan 3 or 4 hectares of forest). But what has been even more challenging, until now, is translating these billions of data points into meaningful measurements.

“For a long time, it’s been a real bottleneck processing the raw data into ecologically interesting information,” says Dr Lines. “The images might look pretty but we want to know what species they are, how much carbon is being stored there, what kind of habitats they’re providing, what kinds of microclimates they’re controlling, what species they are supporting so we can use that data to value the forest.”

The latest developments in AI and machine learning have been a game-changer for Dr Lines and her team – taking the manual labour pinchpoint and fast-tracking the data processing so that they can monitor essential biodiversity variables (EBVs) that measure the value of biological diversity.

“What we have been finding is that AI is an incredibly powerful tool to help us get from the raw data into ecologically interpretable information,” she says. “We can use information from individual trees to work out things like the canopy coverage and the leaf area and that helps us to calculate carbon storage and sequestration.”

This incredibly detailed analysis can now be done at the flick of a switch, saving hours of researchers’ time.

“AI allows us to separate different materials within our point cloud,” Dr Lines explains. “It really enables us to scale the study. We could do all of those things at a very small scale before, but things that were taking us weeks and months before are now taking just one afternoon. We just need to press a button and check the results.”

In the past, a lot of Dr Lines’ research involved hiking through forests and measuring trees manually with a tape measure. And to make fieldwork even more challenging, many of the most interesting forests ecologically are in highly inaccessible places. Using manual measurements also involve a lot of assumptions, for example, when it comes to calculating how much carbon each tree was storing. The powerful combination of drone technology, remote sensing methods and cutting-edge AI tools has transformed the way the team works – and it’s proving to be incredibly accurate.

“For me, it was really exciting to find technology that allowed me to actually get a much more direct measure of so many aspects of the tree function than these traditional methods,” says Dr Lines. “When we fly drones, we capture hundreds to thousands of trees in one flight, which would be days and days of work on the ground.”

“The technologies allow super accurate carbon measurements,” she says. “There’s been a lot of work where trees have been scanned and then they’ve been cut down and weighed. The accuracy is very high in terms of working out how much carbon is in them. That’s been a really key application of these technologies and the more we can do and the larger the scale, the more we can do for carbon storage.”

Making sense of the data

Making sense of the data is no straightforward task. Research Associate Dr Harry Owen and PhD student Matt Allen have been working with Dr Lines to build AI models from scratch to classify the data points for each tree to help reveal how much carbon is stored and where microhabitats are formed. This has huge potential for conservation and monitoring in future, according to Dr Lines. They have already used this approach to detect and map diseases like ash dieback as well as documenting the impact of drought – and has the potential to help provide stronger evidence for policies and programmes addressing climate change in future.

However, this pioneering approach to conservation monitoring is not without its challenges. One of the remaining bottlenecks facing Dr Lines and her team is the huge amount of data that AI needs in order to train the model to be as accurate as possible. This involves labelling each data point gathered so that the AI algorithm can recognise different parts of a tree – down to the tiniest leaf and twig.

“We have this three-dimensional editing software where you can use little scissors and cut out point by point or cluster by cluster,” says Dr Lines. “It’s really challenging to do and obviously, if you don’t do it well, you’re not going to train your model well. But we think pre-training is a really promising deep learning technique to help us overcome that.”

Collaborating with other teams across Europe and around the world is going to be key to make sure the AI model is trained on diverse data sets – covering all the major biomes and ecosystems.

“We are taking a very community-driven approach,” says Dr Lines. “We’ve got small amounts of very high-quality data and many of our collaborators have the same. So by bringing them together, we can tackle these problems at a larger scale.”

Dr Lines’ recent project brought together individually labelled data from 20,000 trees across Europe, drawing on contributions from a wide network of collaborators to develop highly accurate models for species detection. Looking ahead, she hopes that the relatively affordable drone technology her team has been using to gather tree data can be adopted by landowners and land managers to support large-scale land monitoring and biodiversity assessment.

“There are farmers using drones to do things like track their cattle or livestock,” says Dr Lines. “There’s lots of interest in high precision remote sensing for identifying when nutrients need adding to soil or when crops need irrigating. So already there’s a lot of this sort of technology in the agricultural and land management sector.”

“The aim of this project,” she says, “is really to open up these technologies for use by non experts. We think that putting the technology in the hands of the people who manage land and own the land is really important when we’re thinking about doing biodiversity credit and carbon credits well.”

Dr Lines’ pioneering project is one of several cutting-edge collaborations that have received support from ai@cam’s AI for climate and nature initiative, which is bringing together people from many different fields to address the most urgent environmental challenges.

“My own background is in mathematics and then I did a PhD in ecology,” says Dr Lines. “My team is typically half engineers and computer scientists and half biologists, psychologists, geographers and other specialists. It is by working together, bringing those groups together, that we make the most exciting progress in this area.”

“3D forest tech laser scanning is quite a niche field in itself,” she adds. “But I think all of us believe that this is the future of processing these data sets.”