AI is reshaping the way we access and interpret cultural heritage collections, from transcribing fragile manuscripts to piecing together fragmented artefacts. At Cambridge University Library, Dr Amelie Roper and her team are leading the AI for Cultural Heritage Hub (ArCH) project, a new initiative exploring how AI can reveal hidden collections while placing expert knowledge, ethical practice, and sustainability at its core.

What was the inspiration for the AI for Cultural Heritage Hub (ArCH) project and what was the gap that it aims to address?

The AI for Cultural Heritage Hub (ArCH) grew out of two main inspirations: the untapped potential of the vast and diverse collections across Cambridge’s libraries, archives, galleries, museums, and herbarium - many of which remain underexplored - and the belief that cultural heritage should be accessible to everyone, whether it that be for research, inspiration or enjoyment.

The project aims to create a secure, replicable workspace (the “hub”) that will enable non-technical users - those working in galleries, libraries, archives and museums, and academics without any specialist technical expertise - to analyse cultural heritage data securely with AI tools. Cultural heritage data means data about the items held in cultural heritage collections. The most typical types of data are collections metadata (descriptions of items in collections) and digital images of collection items.

ArCH addresses the lack of a secure “sandpit” where AI tools can be used on cultural heritage datasets using workflows that are accessible to those with limited technical expertise. The hub’s infrastructure will be open source and built on internationally-recognised standards, ensuring that it can be reused, scaled, and further developed by others. Beyond the technical platform, ArCH is also fostering a community of practice, through events and workshops, to surface common challenges, and build confidence in the responsible use of AI for cultural heritage collections.

How does it tackle some of today’s major challenges when it comes to GLAM institutions (galleries, libraries, archives, and museums)?

Cultural heritage organisations around the world hold billions of items that remain inaccessible. While there are many reasons for this, one of the most fundamental is that vast numbers of items are simply not discoverable. In many cases, no publicly available descriptions exist, leaving objects effectively invisible to anyone outside the institutions that house them. Even when items are discoverable, they are often preserved in formats that are difficult to access or do not meet users’ needs. For example, a manuscript may need transcription or an artefact may survive only in thousands of fragments that are impossible for humans to piece together unaided.

ArCH is tackling the accessibility of collections by focusing on three core challenges.

- Challenge 1 is unlocking inaccessible data by using AI transcription and computer vision tools on digitised documents. While transcription can be carried out manually, the vast scale of untranscribed material, and the time required to process it, far exceeds the staffing capacity of most cultural heritage organisations.

- Challenge 2 is reconstructing fragmentary or dispersed cultural objects, enabling new insights into their form, meaning, and historical context.

- Challenge 3 is embedding expert cultural knowledge into AI algorithms, drawing not only on academic expertise but also on the knowledge of practitioners and communities connected to the collections.

Are there any potential risks of using AI in the cultural heritage sector?

Our main concerns have been around quality control and reproducibility. AI-generated results can vary, and at scale these challenges become even more complex. Having “humans in the loop”, including cataloguers and curators alongside academics, is essential in addressing this and for validating outputs. In practice, AI is rarely able to deliver a complete or definitive answer to complex research questions. It works best when questions are broken down into smaller tasks and guided by expert knowledge and targeted testing.

Another risk stems from AI’s reliance on digitised material. Most institutions have digitised only a fraction of their holdings, so results may be biased or unrepresentative if the quantity is too narrow. While ArCH has been able to digitise some additional material with support from ai@cam, this may not be the case for all institutions. There is also a danger that, when working with AI at scale, we overlook what is distinctive and irreplaceable about individual collections. AI is best viewed as a tool to enhance discovery and interpretation, rather than a replacement for direct engagement with original materials.

Finally, there are key environmental considerations. Training and running AI systems consumes significant energy, yet the GLAM sector currently lacks reliable tools for measuring these impacts. With sustainability becoming an increasing priority in galleries, libraries, archives, and museums, understanding and addressing the environmental footprint of AI is critical.

How did you get involved in this line of research?

I am currently Head of Research at Cambridge University Library, where I manage the University Library Research Institute (ULRI), a centre dedicated to collections-led research. ArCH is one of several projects within our portfolio.

My background is in collections-based research, including a PhD in book history, and I have held a variety of roles in special collections in libraries. From the very beginning of my library career, I have been interested in how technology can be applied to libraries and committed to making collections accessible to diverse audiences. One of my first jobs involved converting typescript catalogue cards into MAchine Readable Cataloguing (MARC) format so that they could be searched via an online catalogue. It is fascinating to see this work come full circle, with one of ArCH’s case studies now exploring how AI can be used to transcribe and structure data from card catalogues.

As a researcher and librarian with a humanities background, I was initially apprehensive about leading what might be considered a technical project. However, as ArCH has progressed, I have come to appreciate how the critical thinking, communication, and documentation skills I developed as a historian, together with my practical experience of working with heritage collections, are real assets to the project.

What challenges have you faced so far throughout the project?

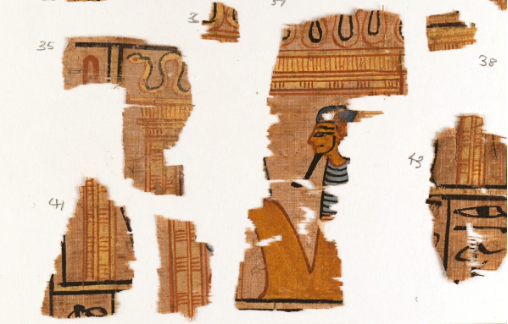

One of the biggest challenges of the ArCH project is logistical. It is a fast-paced project that involves working on six different case studies in order to develop the hub. Each case study is reliant on a different combination of team members and collections: card catalogues and a Mesoamerican pictographic lectionary at Cambridge University Library; specimen labels at the University Herbarium; accession registers and notebooks at the University Museum of Zoology; the Book of the Dead Ramose at the Fitzwilliam Museum; and scrimshaw materials (objects made or decorated by people involved with the whaling industry) at the Scott Polar Research Institute. Coordinating all six case studies and ensuring steady progress while balancing the availability of team members across multiple institutions requires careful planning and organisation.

From a technological perspective, one of the biggest challenges lies in creating a secure, replicable environment where AI can be applied to collections data. Cultural heritage collections often contain material that is sensitive for many reasons, including copyright, data protection, licensing restrictions, subject matter, materiality, and provenance. Cambridge University Library’s strong track record in building secure systems for digital collections gave ArCH a solid foundation for developing a workspace with individual logins for users. However, controlling how uploaded data is subsequently used by AI engines - and ensuring it is not retained for training - remains a much more complex task.

Could you tell us about the interdisciplinary project team you are working with, and how it draws on expertise from across the University?

ArCH is a collaborative project led by Cambridge University Library, working with the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics and the Collections, Connections, Communities strategic research initiative. Our team includes 16 members, bringing together cultural heritage practitioners, digital humanities specialists, AI experts, developers, and academics.

Although my role at the University Library Research Institute connects me with colleagues across Cambridge and beyond, ArCH has given me the opportunity to work with them in a much more sustained and meaningful way. Working in such an interdisciplinary team has been one of the real joys of the project. My colleagues Jennie Fletcher (Lead Developer) and Tuan Pham (Digital Transformation Programme Director) have been especially central to building the hub - it simply wouldn’t exist without them. At times, we need to pause to make sure we are “speaking the same language,” but that effort always pays off, leading to shared understanding and more innovative results.

I feel privileged to be part of the ai@cam initiative. When I began my career in libraries, I never imagined I would lead a project like this. It is inspiring to work with colleagues to explore how AI can tackle challenges faced by cultural heritage organisations worldwide, and the support from ai@cam, whether technical or through new research connections, has been invaluable in helping ArCH grow and thrive.

What partnerships are you hoping to create or draw on as part of the project?

Partnerships are at the heart of ArCH. Within Cambridge University Library we are collaborating across teams that include developers, digital humanities specialists, curators, cataloguers, and researchers. Beyond the Library, we are working with collections experts and academics from across the University and further afield. Our case studies involve researchers at Birkbeck, University of London, and the University of Liverpool, while our advisory board brings together representatives from the wider cultural heritage sector.

Looking ahead, our vision is that once the hub is fully developed, galleries, libraries, archives, and museums worldwide will be able to implement their own versions to use with their collections, making cultural heritage more discoverable on a global scale.